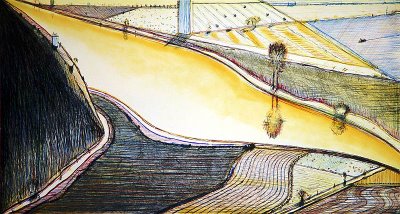

"A Walk with Ganesh"

Gregg Chadwick, 72" x 84" oil on linen 2005

My brother,

Kent Chadwick, is a Seattle writer and recently finished a poem inspired by the painting above:

"A Walk with Ganesh"

Obediently, I begin, but it is a curious

way to experiment with no design

and venture out in thought alone.

It is my father who has traveled to where elephants

wander, to where they’re worked and tended.

It is my brother who has breathed the red

dust of Bangalore, who was told

by a Bombay cab driver,

“Ganesh was just in my car!”

At home I know just what I read—

that he broke off a bit of his tusk

to take dictation, to copy

down at divine speed

the inspired, sculpted rush

of Ved Vyasa’s verse

creating the Mahabharata.

Oh, to compose as swiftly

as a god can write!

Oh, to out sing one’s breath!

Obediently, I begin a journey

measured in mouse steps—

a journey inside—to that seam

between animal and god, those stitches

holding our incongruousness together.

A seam like the one his mother’s

husband made with a sword:

Shiva, angered, striking

off the head of this unknown lad

who blocked the door to the bath,

the boy Pavarti made

from the sluff of her body herself

to guard her door, her honor.

Remorseful, Shiva sent

his retainers to find another.

They found an elephant by a stream,

sacrificed the young bull—

it’s blood flowed down to the water,

dyeing the fair stream—

and they carried back its proud

head of tusks and trunk,

which Shiva joined to the lifeless

body of the boy, reviving

him, making him god of beginnings,

Ganesh, remover of obstacles,

Ganesh of a mother’s love.

How swiftly we pull our swords;

how often cry out in sorrow.

Obediently, I follow Ganesh

into my head, my memory, my past.

He knows where he is leading, with no hesitation

takes me back to the bare

hills of Southern California:

their sage and tumbleweeds,

tan grass alive

with beetles, horned lizards,

red diamondbacks.

Vultures soaring and seeking

over the arroyos; the chaparral baked

in the sun’s blue kiln;

the wind’s warm fragrance

dryly whispering, “Thirst.”

“Why this place?” I ask.

“Isn’t this your imagined golden land?

What better place to see the story you are to sing?”

To sing?

Oh that this god would grant sweet lyrics.

On a path of sandy loam,

quartz, fool’s gold,

we crest a hill of oaks

and see below us Combat Town.

The idylls forming in my head

of surf and sand and love

disappear with the smell of spent

shells and smokeless powder.

This is the place we played as boys,

among the cartridges, K-ration

tins, ammo boxes,

scarred earth and walls,

mimicking our fathers’ skills

in killing the enemy and saving

their own. This is where we acted the lucky

hero whose M-16

clip never empties, who captures

the flag and comes back

home unscathed, victorious.

This was Combat Town circa

1963

arranged as a Vietnamese hamlet

with sweeping roof lines,

open air market,

even a pagoda, which is where Ganesh heads,

a pagoda without sutras, built

not to house a holy scripture

but for training in combat tactics,

hollow like all the buildings in this town.

On the ground floor Ganesh

sits his great body

into position, folded supplely

for meditation, his elephant head

echoed in the carvings on the pillars

of animals of power—elephants

and tigers—verisimilitudes

the Architect had insisted on.

What powerful tremors,

what earthshaking silence

flows from the meditation of an enlightened one.

I look out the empty windows

of the bullet-pocked pagoda

and see Combat Town

fill with young recruits

fumbling with their rifles, confused

on how to move, how to follow orders

that their drill instructors shout,

blushing when the war game

officer marks their helmet:

“You’re wounded. You’re dead. You’re hopeless.”

And time accelerates around Ganesh:

the recruits run through their drills,

day upon day losing

their awkwardness, reflectiveness, weakness,

becoming stronger, fiercer, obedient,

ready to aim and fire.

The anger, fatigue, and repetition

carve a soldier’s instincts

into their psyche, setting the triggers

that when needed will help them kill

and survive, save their buddy,

bring their unit honor.

Then the rounds’ sound changes

to live firing. It’s Vietnam

before me and those same recruits are blooded warriors

now moving through a hamlet safely

separated, poking the dead,

silencing any hut that returns

fire, questioning the headman

in pidgin about when the V.C.

came and where they ran to, believing

only half of what he says or what they see.

And when their patrol moves on, the local

Viet Cong lieutenant

climbs out of a tunnel

below the headman’s home

with the men and women from his squad

he’s saved and they slip away.

The Marine patrol comes

back through the hamlet in another week.

The corporal on point spots

the mine, signals a halt.

The men crouch anxiously.

With no explosion to begin their ambush

the hidden Viet Cong

start firing separately,

yet are killed quickly by multiple

streams of automatic fire.

One of their rounds, though, tears

off the corporal’s jaw—a gaping

wound where his mouth had been.

The sergeant pulls him to cover

by his ankle, his broken face

dragged oozing over the dirt.

His buddy crawls to him and stabs

syringes of morphine into his leg,

wraps his head with gauze.

When they finally secure the hamlet

they force the villagers out of their homes

and huts and fields, push

them out on the road carrying chickens

and children, leading their buffalo,

warning them not to turn back—

“Go! Go! Don’t look!”—

as a Thunderchief delivers

the napalm strike exploding

as a white fireball

burning everything they’ve known.

“It is a great sin,” Ganesh says,

“to ever imagine destruction as a cleansing.”

Through the acrid smoke I watch

the Architect directing changes,

reshaping Combat Town

by blueprint, desperate

for a stratagem that will win the war:

strategic hamlets, truces,

carpet bombing, mining

Haiphong Harbor, interdiction,

Vietnamization, invading Cambodia.

But every advantage leads to losses

and the helicopter evacuation of Saigon.

Combat Town quiets down

for a season. But then new blueprints

are drawn and the pagoda we are in becomes

a Central American church

and wars later is rebuilt to be a mosque.

And the weapons the recruits learn

become smarter and more deadly, as do they.

And when Ganesh rises from his meditation,

and I am ready to leave this dream,

he chides me and leaves me there to stay,

saying, as he rides his mice away,

“This is your story, no?

America’s story.

A story of continuing war.”

— Kent Chadwick